The Nuts and Bolts

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

What are the differences between blobs trees and objects?

Objectives

Understand the terms blobs, trees and objects

Know how git uses them to store data

Understand why we can never change git history, only replace it

Git Objects

Git stores everything it knows about your changes and history in a database called the object database.

First, we’ll navigate to the material for this episode:

$ cd ~/git-demystified/episode_3

And take a look at the content:

$ git log --all --oneline --graph

This is the same merge from the end of the last episode.

* 8339406 (HEAD -> phantom-tracker) Merge branch 'another-phantom-tracker' into phantom-tracker

|\

| * b7945fb (another-phantom-tracker) Added phantoms

* | cbfc473 Added phantoms

|/

* cd3a38a Phantom commit

| * 6ec2577 (master) Changes

|/

* e93c765 Added colour specification and blue.txt

* 805a6c8 Add lists of red and green objects

Let’s take a look at the objects that git knows about:

$ find .git/objects -type f

This is a UNIX command to find every file in the .git/objects directory. There are quite a few.

Let’s look in particular at .git/objects/6e/c2577e32f1e4484f098a97656ca7bd62800596

Don’t try to look into this file with cat, it’s a compressed binary file which won’t be readable. Git gives us a special command to decompress the content.

$ git cat-file -p 6ec2577

tree 866cc5a7af96b7636c74588b110624379860d42e

parent e93c765e847e46a9200d43ff7ef7115b3c7c486b

author Mark Dawson <mark.dawson@swansea.ac.uk> 1577869200 +0000

committer Mark Dawson <mark.dawson@swansea.ac.uk> 1577869200 +0000

Changes

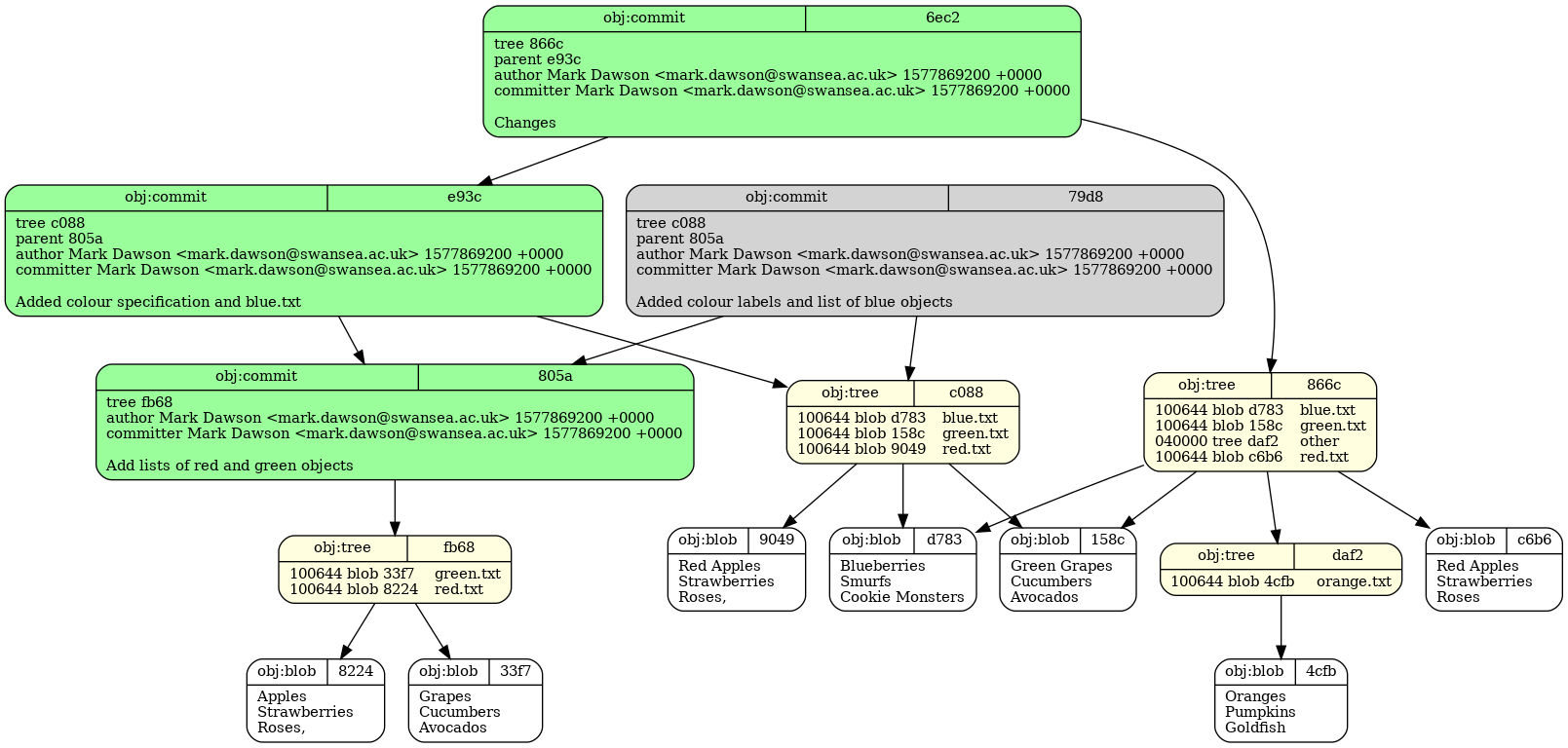

This is the commit “Phantom commit”. It seems to have a reference to a tree object (866cc5a) and a parent (e93c765). It also has the author, timestamp and commit message.

We can follow these idenifiers again with git cat-file -p:

$ git cat-file -p e93c765

Shows the previous commit

tree c08804ed275c9118e61a36966039acc2c750ad33

parent 805a6c841c5a2e464fbcc671fa651bca811c2abc

author Mark Dawson <mark.dawson@swansea.ac.uk> 1577869200 +0000

committer Mark Dawson <mark.dawson@swansea.ac.uk> 1577869200 +0000

Added colour specification and blue.txt

Both commits have a tree object. This is the root of the tree in the HEAD version of the three trees as it was when this commit was created. Let’s take a look at the one for “Phantom commit”.

$ git cat-file -p 866cc5a

100644 blob d783f04d417b22a5fdbf369c418203d5f9173e37 blue.txt

100644 blob 158c5d5d8b0bf4fdbe817c9320275ec38f75fe35 green.txt

040000 tree daf27696e906b6663e4cb8601a96b04aca27eee0 other

100644 blob c6b61f8fd1e47b30a21de6db1841bd71f7e340d2 red.txt

This looks like a listing of file and folder names. The folders are tree objects, and the files are blob objects.

Let’s look at one of the blob objects, blue.txt for example

$ git cat-file -p d783f04

Blueberries

Smurfs

Cookie Monsters

For a simple version of this lesson, such as the state of the repository at the end of the first episode, we can look at all the objects.

Content-addressable Storage

Git is fundamentally a content-addressable file system with a version control system user interface written on top of it. - The Pro Git Book

So what is a content-addressable file system?

This is a system in which the names of files are directly determined by their content. We take a fingerprint of file content before we write it, and use that as the file name. In this system, every single object with the same content, goes in the same file, and is by definition the same thing.

Any file which contains

Green Grapes

Cucumbers

Avocados

in any git repository in existance will always be stored in the file .git/objects/15/8c5d5d8b0bf4fdbe817c9320275ec38f75fe35.

In git, this is true of blobs (file content), tree (file names and directory structure) and commits (metadata about commiting)

Since commits are made from blobs and trees, which in turn are made from blobs - this effect bubbles up. If two commits have the same ID, this is an very strong guarantee that they’re identical, include all the content in all the files and all the history of commits, and the content in all those commits. In practice, this turns out to be very powerful.

Bubbling up

The converse is also true however. If the content of a blob changes (e.g. by changing the content) then the ID of that blob changes by definition. In term, consequentially, the tree and commit IDs will be different. Note, since every commit references the parent, all child commits will also need to change. Likewise if a tree changes (by renaming or moving files or directories), then the commit and all of its parent commits will change. It has been noted that git is a content-addressable filesystem, with a version control system build on top of it.

Mutable blobs

Look at blob

4cfbin the diagram above. Imagine that this is replaced in a commit by different content. What else objects would need to change for the commit “Changes” to have identical content, but with this one object changed?Solution

- The contents of tree

daf2would change since it contains the ID of the blob.- Since the contents changes, the ID of the tree also changes (which by definition would now be a different tree)

- This causes the content, and therefore ID of

866cto change - creating a new tree- The tree identifer in the top level commit would change, which in turn would change the commit identifier.

- There would be a new commit identifier, with some blobs shared with the previous example.

Almost all

Not all things git knows about are objects. Branches, the HEAD pointer, the staging area (or index) and tags are information that git holds which are not objects.

Commit-ish and Tree-ish

In documentation you might see many references to things that are commit-ish or tree-ish. Git has a powerful translation mechansim, that can convert any number of differnt ways of referring to a commit into a commit object or tree obeject (if it needs them). We say these different ways of references commits or trees are commit-ish or tree-ish. Examples of this that we’ll see today would be:

$ git checkout masteror

$ git checkout HEADmost of the time, git is simply looking up the commit that master or HEAD currently point to, and performing the operation on that commit.

So, anything you do to change a commit in any way will result in a new commit with a different ID, even if all the contents is the same but only the commit time is different, it will be a different ID.

Branches

Each commit is some metadata about the author, a pointer to files/contents, a commit message and a pointer to the previous commit. This creates a chain of commits extending back in time. We could imagine how we could follow this chain back to the start if we know the last commit. This is exactly what a branch is, a pointer to the latest commit.

Finding trees

First, consider would you expect the top level directory tree of this commit and the last commit to be the same or different? Verify your guess using

git logandcat -p <thing-id>Solution

- use

git logto find the ID of the current and last commits (the 40-character string in git log).- write down the first six characters of both, let’s say (for example) they are

a12345andb56789.git cat-file -p a12345will then show you the commit content. This will contain the tree IDgit cat-file -p b56789will then show you the commit content of the second commit.- Compare the ID shown for tree in both.

Finding blobs

Use

git cat-file -pto see the content of both trees from the last excercise. What can you tell about which files have changed and which have not from the tree? Did this match your expectation? Does the blob ID change for files which have the same content?Solution

Files with the same content should have the same blob ID in the tree. Files with different content will have different blob IDs.

Key Points

Used

cat-file -pto explore blobs and objects