Understanding Add and Commit

Overview

Teaching: 45 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How do we really create commits?

Objectives

Review of git add and git commit

See how git creates commits

Explore the three trees

In this episode, we’ll discuss the basics of adding and commiting files. We will however take great care with the mental picture we create git commits. This mental picture might be different from the way in which you’ve thought about git in the past, but understanding it is first step to truly understanding git.

Setup

Assuming that you’ve downloaded the lesson material to the directory ~/git-demystified, we can

change into the directory for this episode with:

$ cd ~/git-demystified/episode_1

In this episode, we’ll discuss the basics of adding and commiting files. We will however take great care with the mental picture we create git commits. We can see the files in this folder or directory with:

$ ls

We can look inside one of the files with:

$ cat blue.txt

Which will give us the output:

Blueberries

Smurfs

Cookie Monsters

The other entry in ls a folder, we can look inside with:

$ ls other

So far, this is just a plain directory with files. Let’s initialise it with

$ git init .

Changes as Differences

Let’s start by reviewing what we might think about add and commit so far.

We’ll start by add the file red.txt

$ git add red.txt

Finally, we’ll have a look at the status of files with:

$ git status

We’ll see the output

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: red.txt

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

blue.txt

green.txt

other/

When you’re starting out, it’s helpful to think of git add as adding the changes that you’ve made to a file to the staging area. But we’re going to be looking at a more accurate and useful way of thinking about this later in this episode. For these simple actions, both these approaches are equivalent.

For more advanced usage however, this mental model breaks down quickly. We need to unlearn this way of thinking and learn to think of git in terms of snapshots. This will be the topic of the rest of this chapter.

The Three Trees

Git is often described as manipulating trees of files, you can think of them as three folders.

These are:

- The

working directory- your current git files - The

staging area- where you prepare the next commit - The current commit or

HEAD- the current commit, the one you’re building on top of.

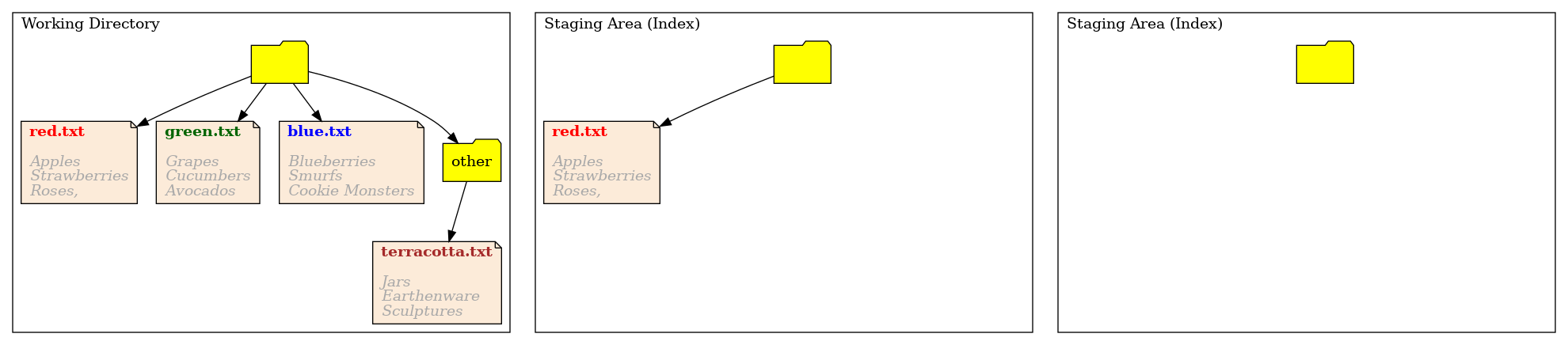

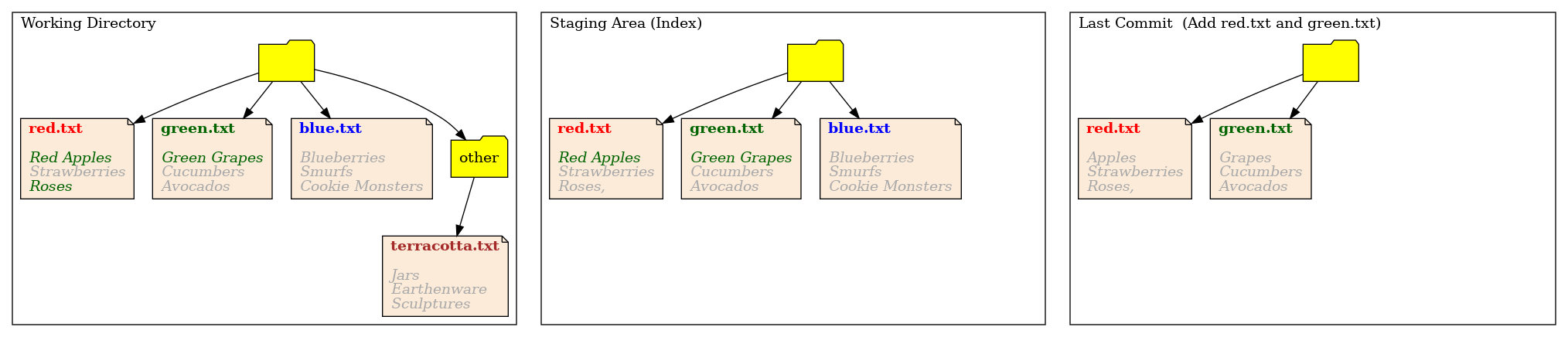

The following images shows how these three trees looks currently after adding red.txt to the staging area.

Git add has copied the file red.txt into the staging area. It hasn’t done anything more complicated than that. This is how git stores the changes we’ve made.

Lets look at the output of git status again:

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: red.txt

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

blue.txt

green.txt

other/

It seems like git status is in fact a summary of the differences between HEAD and the staging area. Git computes this on the fly when you call git status, which is why git status can sometimes take a long time in a very large commit.

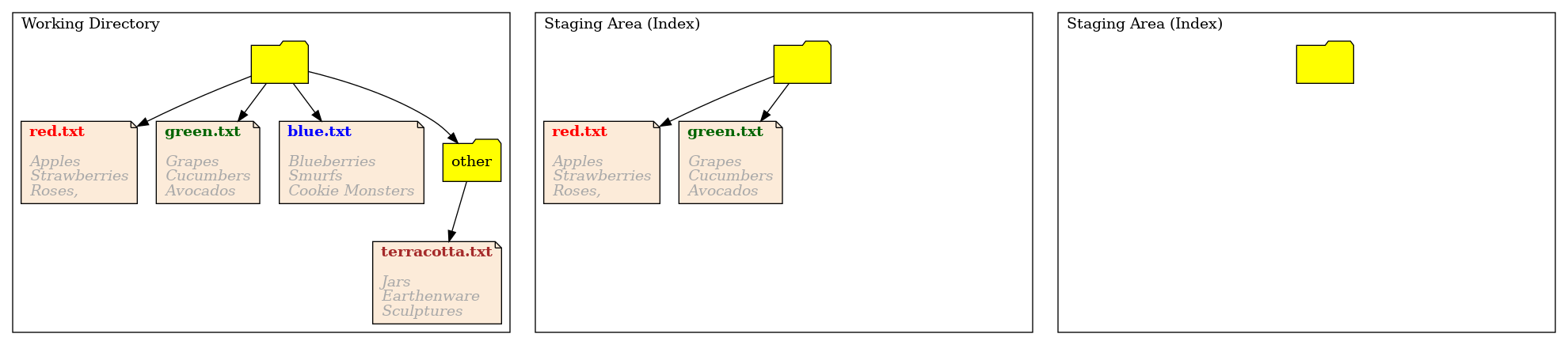

Next we add the file green.txt:

$ git add green.txt

Now the staging area changes, but the working directory and the last commit stay the same. Remember that git add it a copy. The staging area now looks like:

Once again, if we typed git status it would summarise the differences between the staging area and the commit.

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: green.txt

new file: red.txt

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

blue.txt

other/

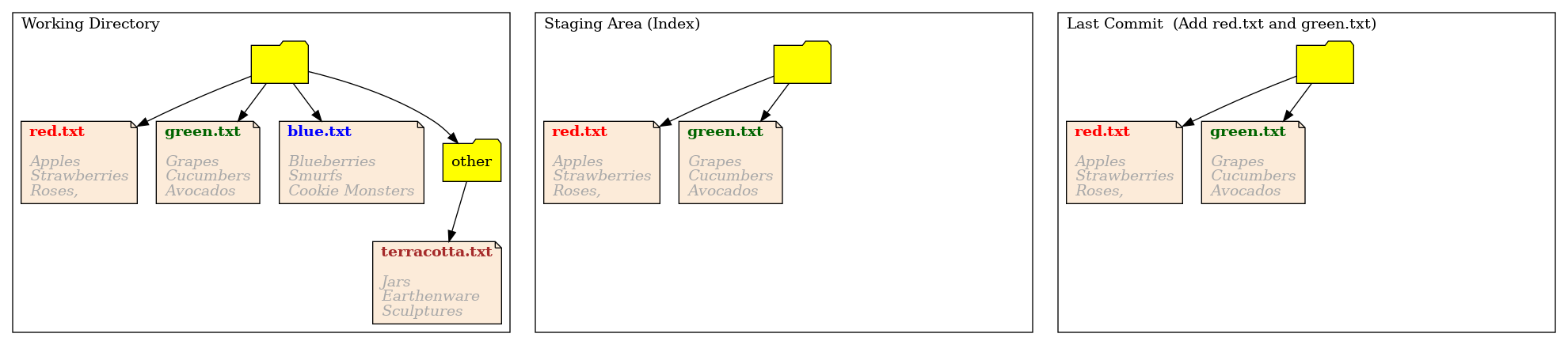

Now lets create our first commit

$ git commit -m "Add lists of red and green objects"

The only thing that changes here is the current HEAD. Git took the staging area, the next proposed commit, and made it the current comit. It did this by first storing the previous commit away somewhere. Then replacing this with a copy of the current staging area, making that the current HEAD commit.

Keeping history

Note that we clearly don’t overwrite the previous commit. Imagine putting the previous commit in storage somewhere, and replacing it with the contents of the staging area. We’ll discuss how this storage works later.

Let’s take another look at git status

$ git status

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

blue.txt

other/

Git reports on the untracked files, which are the files which have never been added to the staging area. There are no other differences to report.

Note how the commit contains a complete snapshot of all files, as if you had copied them there by hand.

Also, note how the staging area contains the previous files, not just the changes we’ve made in this commit.

Crafting commits

Let’s make some changes in the working directory, by editing the files. First we’ll edit red.txt, changing Apples to Red Apples and changing Roses, to Roses (removing the comma). We’ll do this with:

$ nano red.txt

Then we’ll edit green.txt changing Grapes to Green Grapes:

$ nano green.txt

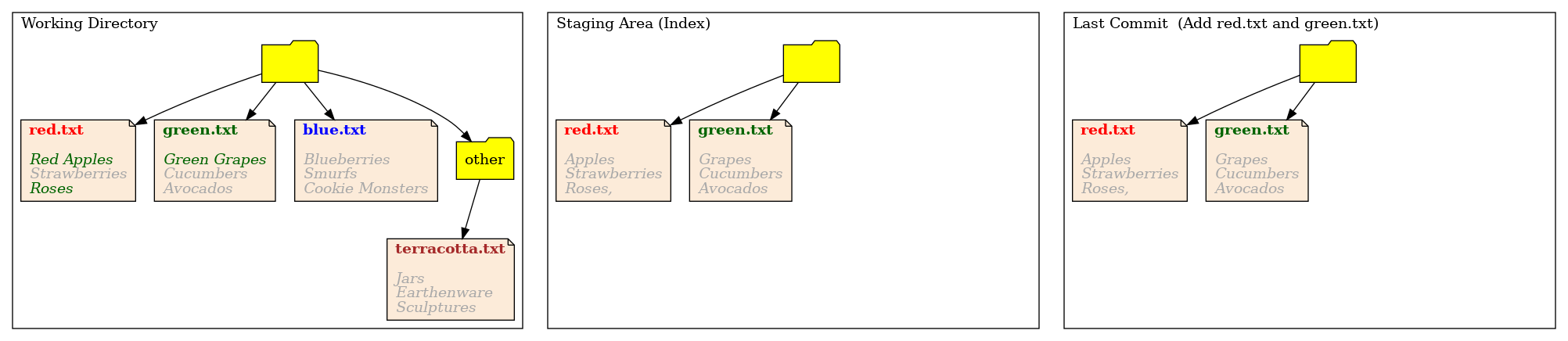

The working directory now looks like, we’ve highlighted out changes in green:

We’ve made all these changes at once, but let’s turn this into distinct commits:

- One commit that adds the lines which correct typographical erros

- One commit that adds the file

blue.txt, and updates colours

Normally, we would avoid adding two distinct changes to the same commit. But we’ll come back and fix this later.

To add the typographical error, we need to add only part of a file. We can do this with

$ git add -p red.txt

We select s to split the hunk that git presents us with, y to accept the first change, and n to reject the second.

Next we add blue.txt and the changes from green.txt

$ git add blue.txt green.txt

Finally, we check that status:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

new file: blue.txt

modified: green.txt

modified: red.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: red.txt

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

other/

Note how red.txt appears in both sections.

We can see explicitly what is still not staged with:

$ git diff

By default, this shows the differences between the working directory and the staging area.

We can see an explicit diff between HEAD and staging area with

diff --git a/red.txt b/red.txt

index 90498cb..c6b61f8 100644

--- a/red.txt

+++ b/red.txt

@@ -1,3 +1,3 @@

Red Apples

Strawberries

-Roses,

+Roses

In this case, it would be more useful to see what it about to make it into the next commit. We do this with

$ git diff --cached

diff --git a/blue.txt b/blue.txt

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..d783f04

--- /dev/null

+++ b/blue.txt

@@ -0,0 +1,3 @@

+Blueberries

+Smurfs

+Cookie Monsters

diff --git a/green.txt b/green.txt

index 33f7e97..158c5d5 100644

--- a/green.txt

+++ b/green.txt

@@ -1,3 +1,3 @@

-Grapes

+Green Grapes

Cucumbers

Avocados

diff --git a/red.txt b/red.txt

index 8224889..90498cb 100644

--- a/red.txt

+++ b/red.txt

@@ -1,3 +1,3 @@

-Apples

+Red Apples

Strawberries

Roses,

The git diff --cached command shows, if we did commit now, how would the resulting commit be different to the current commit.

Let’s take a look at how our three trees look at this stage:

Note how git -p has created a file in the staging area, from the instructions we’ve given it, in a state in which the file has never existed in the working directory.

We’ll now commit this

$ git commit -m "Added colour specification and blue.txt"

Let’s take a look at our log

$ git log --oneline

Note how git gives us an identifier for each commit, and that the identifiers on your machine are different to mine.

Everything else

Finally, we’ll commit everything that is left with

$ git add red.txt other/

$ git commit -m "Changes"

This will copy all the files from out working directory into the staging area, then create a new commit which will also be identical to the working area. After doing this, all three areas will be the same.

We can verify this with

$ git status

Patching

Make as many changes as you like to any files you like, making sure to make multiple changes to the same file. Use

git add -pto create multiple commits that each contain only some of the changes. You can practice:

- choosing sections to add/remove to a commit with y and n

- splitting up changes grouped together using s

- splitting up changes on the same line into different commits using e

Key Points

Git add copies files into the staging area

Git commit creates a new commit by duplicating the staging area

Git status shows a summaries of differences between the trees

Commits are not overwritten, they’re stored somewhere and replaced